Broadly, I am interested in understanding patterns and drivers of urban forest structure, diversity, and health. To be more specific, I am interested in understanding why some areas have more trees in others, why the trees in some areas are healthier than others, and how those two patterns have changed over time. This requires us to look at the physical conditions that trees grow in (i.e. their rooting space, land use) as well as broader social and political conditions that inform tree planting, tree care, and more.

My focus to date has primarily been on street trees, which face some of the most challenging growing conditions within cities, and on physical growing conditions. However, building on some more recent theoretical frameworks, I hope to expand to look at urban forests more generally and get deeper into the social and policy drivers of urban forest structure.

Biodiversity and the Luxury Effect

The field of urban ecology has been interested in understanding patterns in biodiversity for decades. One of the patterns that has been seen is higher biodiversity found in wealthy areas compared to less wealthy areas. This pattern has been dubbed the “luxury effect.” Though it has been seen in a variety of contexts (especially arid cities and some cities in the U.S.) it is not always the case that wealthy areas have higher biodiversity, and in some cases wealth may not be the dominant driver of urban form and structure.

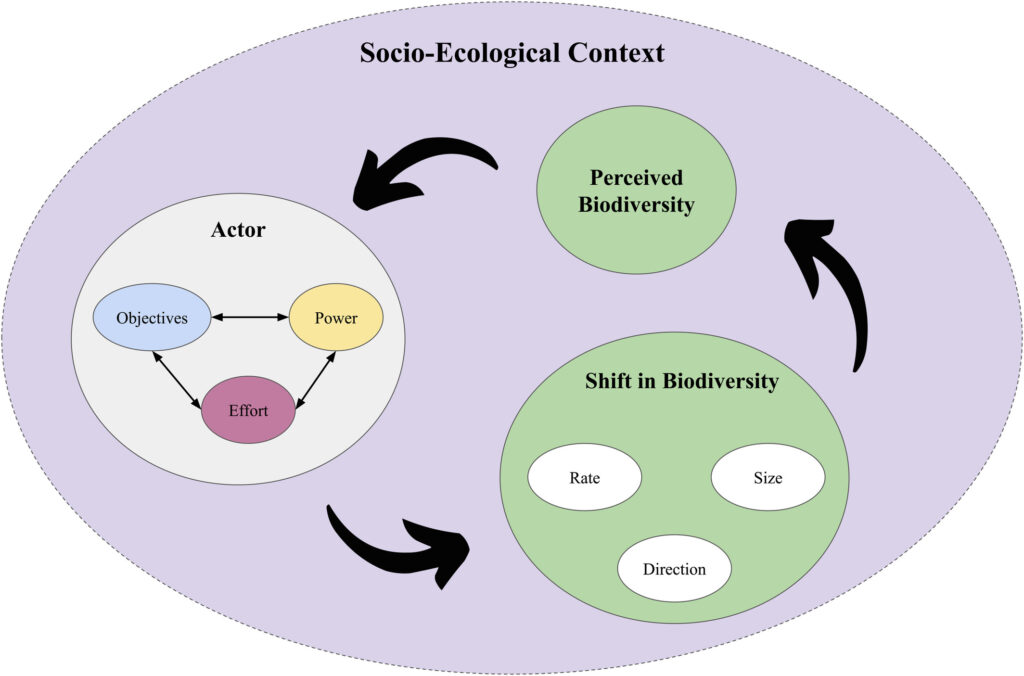

In a theoretical paper (published in Ecosphere here), my collaborators and I outlined an alternative framework to use when investigating patterns of urban biodiversity. This framework suggests that researchers highlight one or a few actors who might be able to influence biodiversity. Then it is easier to examine specific goals these actors have and the actions they take to achieve those goals, including whether or not they have the power to do what they aim. This does not assume that wealth is the main source of an actor’s power or that wealth is automatically associated with a desire for more biodiversity. Instead, it allows for things like popular support, political position, knowledge, and connections to influence whether and how actors influence biodiversity.

I plan to apply a modified version of this approach to developing research projects in my position at The University of British Columbia with the Urban Natures Lab. I will update here as those projects develop.

Tree Number, Diversity, and Health

The focus of my dissertation, defined in collaboration with partners at The Nature Conservancy, was to understand patterns of tree health across neighborhoods in cities. We broke this down into a few related questions:

- How does tree stewardship correlate with tree health?

- How does tree health vary with growing conditions within cities?

- How are patterns in tree health related to displacement from construction and resident turnover?

- How can we observe urban trees to see the impact of droughts

To get at those, we developed three main projects:

Maintenance Impacts on Street and Park Trees (Question 1)

There is not currently a lot of research examining how long-term maintenance impacts tree health and survival in cities; most of the focus has been on the early life stages when a lot of trees die. This literature review aims to clarify what research there is on long-term maintenance, bring datasets from across the globe and see if there are any trends in how activities like mulching, pruning, watering, and pest management impact long-term tree health and whether that varies across regions. For the purposes of this project, we are focusing on street and park trees because there are different dynamics on public and private property, as well as in areas with more individual tree management vs stand-level management.

This resulted in a paper published in Urban Forestry & Urban Greening here in 2025.

Former students on project: Chloe Schueller

Street Tree Health in Durham, NC and Chicago, IL (Questions 2-3)

Street trees have to survive stressful growing conditions due to soil compaction, low-level ozone, physical damage, crowding, and much more. City governments are often responsible for some portion of these trees’ care while residents also do a substantial portion of the maintenance. We aim to see how street tree health varies across Chicago’s west side and Durham, with an eye to the impacts of resident turnover and construction.

This project has resulted in two papers, one that analyzes the data at a tree-level (which has been accepted in the journal Arboriculture & Urban Forestry) and another that looks at the data at a neighborhood-level in the context of gentrification (available here in the journal Urban Forestry & Urban Greening).

Former students on project Evelinn Sanchez, Kamil Orozco, Andrea Nunes, Elizabeth Huang, Lucie Ciccone, Chloe Schueller, Maggio Laquidara

Urban and non-Urban Tree Health During Drought (Question 4)

Drought will continue to be a part of our landscapes and climate change intensifies variability in precipitation and temperature. Trees in cities grow in often stressful conditions; due to these baseline stressors they are likely to struggle in drought conditions. However, these trees also often receive supplemental maintenance (e.g. pruning, mulching, watering) that non-urban trees do not receive, making it possible for them to do better during droughts than their less urban counterparts. However, even within cities, there are likely differences in tree health related to new construction rates, housing turnover, broader land use, and maintenance. We aim to compare the variation in tree health both within cities/across neighborhoods and between cities and neighboring greenspace through time using remote sensing data.

Former students on project: Justin Xavier Smith